When it comes to an ecology of movements, strategies, and tactics, and evaluating different approaches within anarchism and libertarian socialism, it possible to advocate for a plurality of different approaches in a coherent way. Being in favor of a plurality of different approaches and organizations–along with diversity of tactics more broadly– does not merely mean any movement, form, strategy, or tactic makes sense in any context. Ideally such an approach seeks to form a coherent gestalt between different approaches. Communal assemblies, Radical Unionism, Periodic Direct Action, Direct Action Networks, Affinity Groups, Mutual Aid Networks, Cooperative Infrastructure, Popular Education, Anti-Fascism, Community Ecological Technology projects, etc. are all crucial to a revolutionary movement. Such practices fill different niches, and different people like different forms, strategies, and tactics more and less than others ones. Different people will have different skill-sets and different people find different forms, strategies, and tactics more principled/effective/enjoyable than other forms, strategies, and tactics in different contexts (making them more likely to participate in them). Making the argument for an ecology of forms, strategies, and tactics does not mean all ways of approaching all of the above are equivalent (in an extremely strange turn, some anarchists have argued against a “hierarchy of forms/strategies/tactics” which misunderstands both hierarchy and forms/strategies/tactics people can use to arrive at specific or general goals). Various forms and strategies can be described as keystone forms and strategies that disproportionately catalyze other forms, strategies, and tactics, and enable different niches of revolutionary action to be better filled.

Within anarchism there are many internal disagreements–although a signifcant amount of general agreement as well. One of the big distinctions within anarchism is organizationalism vs anti organizationalism. Sometimes this distinction is framed as mass anarchism vs. insurrectionary anarchism, or social anarchism vs lifestyle anarchism. Neo-anti organizationalism in the USA is often against formal organizations not just as a means towards anarchy, but disagree with formal organizations as parts of the ends of anarchy. In some places, anarchist unity has far less tension because organizationalist libertarian socialist tendencies are basically all that exists. In some contexts, anarchism as a movement is so coherent that the issues that will be discussed here will not apply. However anti organizational anarchism did not originate in the USA and the USA does not have a monopoly on it. Arguably, a hard-line stance against formal organization of any kind– that goes beyond mere anti organizationalist means towards socialist ends– is incompatible with the classical anarchist movement. Whether that is the case or not based on how we are analytically or historically looking at anarchism is besides the point. In some places, especially the USA, anti organizationalist anarchists are considered part of the broad anarchist movement (sometimes to significant degrees), and sometimes such anti-organizationalists are against formally organized ends as well-.

Rather than organizationalists being against periodic direct action crews for not being organized enough, or periodic direct action crews being against formal organizing for not being immediately insurrectionary enough, we would be more ethical and effective if we were to acknowledge the insufficiency of various forms, strategies, and tactics we like more–or think are more ethical/strategic– and the necessity or desirability of some other ones. It seems to many that distinctions between formalist libertarian socialist means and informalist action are important and that such formal and informal means are compatible. This can lead many people to call for some kind of “anarchist unity” where different forms and strategies work synergistically together in some way or another.

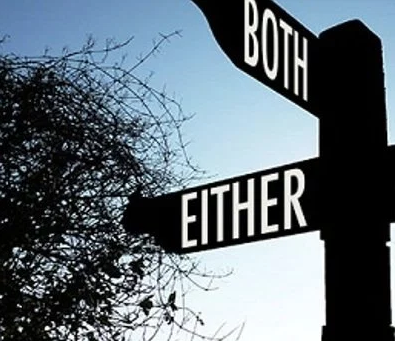

Vague anarchist unity can appear to be a kind of “both and” approach that unites organizationalists and non-organizationalists in a kind of broader movement. In practice, such vague anarchist unity–and associations in accord with such principles– is often an “either-or” between organizing formally and organizing informally rather than a catalyst of both. And the way that the “either-or” plays out is often a reduction to informality and periodicity precisely because such aspects existing in some way or another are relatively uncontroversial between anti-authoritarians (unlike organizational approaches of which are not a lower common denominator between organizationalists and anti-organizationalists). This is because vague anarchist unity reduces unity to lower common denominators between differences in organizational and non-organizational anarchism rather than being a world where many worlds fit.

Given the fact that organizationalists are often–if not categorically– in favor of various kinds of informal and periodic actions, but that anti-organizationalists are against–not just not in favor of– organizational forms of anarchism, the lower common denominator between the two tends towards non-organizational approaches. It is ironically more specific or hyphenated forms of organizationalist anarchism–or libertarian socialism more specifically– that are able to develop a world where organizational and non-organizational worlds fit, whereas vague anarchist unity between organizationists and anti-organizationalists excludes organizationalist dimensions of action in its terms of unity while including anti-organizationalist approaches. By trying to maximally reach out to as many anarchists as possible through lower common denominator unity, some actions needed for revolution (organizational ones) are excluded from practice. More specific kinds of libertarian communism (such as communalism and especifism for example) can arrive at coherence and general popularity in a far easier way than a vague anarchism that is defanged of its organizationalist and socialist dimensions.

Within libertarian socialism, there is general agreement that however important informal and periodic forms, strategies, and tactics are, that we need to build horizontalist institutional power to combat hierarchical relations, meet people’s needs, and build the new world in the shell of the old. There is also general agreement that strategies and tactics–including but by no means limited to informal and insurrectionary strategies and tactics– need to be evaluated within the context of generating libertarian socialist means and ends (because of the way that libertarian socialism is constitutive of the good). It is in these discussions–about when it makes sense to go on the attack for example– that libertarian socialism and informal anarchism can have incompatible goals and ways of evaluating forms, strategies, and tactics. Informalist anarchists and libertarian socialists will sometimes agree on forms, strategies, tactics, and goals, but nonetheless there are important different criteria these different theories have for the evaluation of actions and different goals overall– such as whether organization should even exist as a means and ends of a good society. Even though libertarian socialism is able to provide a kind of “both-and” approach when it comes to formal organizing vs. informalism, it does have different criteria for evaluating informal actions than anti-organizationalism, is in favor of organizational forms, strategies and goals, as well as an affirmation of society itself–which has somehow become a divisive notion in some anarchist circles.