12/15/18

How to Start a Communalist Assembly:

Communalism:

Communalism refers to the means and ends of directly democratic, non hierarchical, ecological, co-federated community assemblies that seek to meet people’s needs, decentralize power, oppose hierarchies, and to build the new world within the shell of the old via libertarian socialist dual power. It is a praxis–an intertwined theory and a practice– that applies universalist principles to particular contexts adapting to relevant conditions and variables accordingly. Communalist assemblies seek to intertwine reconstructive politics, oppositional politics, collective building, principled action, and consequential efficacy–ideally using an ethically principled process strategically to develop goals worth developing.

Forms of Freedom:

Communalist assemblies are rooted in specific practices that qualify the forms and contents of their decisions. The cellular node of communalism–the major form of freedom put forward by communalism–is the community assembly. Communal assemblies are needed for self-management to exist on the community scale. Communal assemblies are places for deliberation and collective decision making about political and economic actions. Community assemblies can have embedded participatory councils/committees/working groups/delegate roles to implement specific decisions within the bounds of the overall decision/policy/mandate/protocols decided by community assemblies. Community assemblies can co-federate to develop inter-communal mutual aid, coordination, decision making, economics, and actions where delegates are sent back and forth between co-federal councils and communal assemblies where policy making power stays at the lowest level in the hands of people directly. In additional to communal assemblies, communalists should favor an ecosystem of popular organizations and social movements that use liberatory means towards liberatory ends.

Constitutions/Points of Unity:

Directly democratic forms are needed for direct collective decision making about what people want to do and about what effects them. However, directly democratic forms can be instrumentalized towards anti-democratic, non-egalitarian, and otherwise unfree content. To avoid such authoritarian form and content, it is important that decisions people make in the assembly–and the assembly form itself– are in harmony with certain liberatory principles. Communalist assemblies have shared practices for political form and content at least include direct democracy, participatory relations, communal self-governance, non-hierarchy, and co-federalism. Such principles can exist as points of unity for shared practice within an organization; existing within the structure of communalist assemblies and existing within the constitutions, bylaws, bills of rights, and programs of a communalist assemblies.

Examples of communalist principles and practices are: Direct democracy, Non-Hierarchy, Co-federalism, Communal Self Governance, and Ecology. Direct democracy within free association of persons, without ruling classes, and without hierarchical relations, makes it so the form and content of assemblies are not towards hierarchical forms and arbitrarily limiting freedoms of persons. Co-federalism allows for interdependent cooperation with other communal assemblies and organizations. Communal self governance is needed for self governance on every scale and to prevent the privatization of politics over and above communities. Ecological praxis is an orientation towards solving ecological problems caused by social problems and using ecological technics. Those general principles that can be applied to particular contexts in a large variety of ways– and can exist within the structure as common practices, processes, and as rights an assembly is designed to uphold and protect. Ideally, some of the people helping to start a communalist assembly should be well versed in the basic theory of libertarian socialism, communalism, social ecology and/or other philosophies and practices based on things like “communal property”, usufruct, direct collective decision making.

Strategy:

The strategy of communalist assemblies is to build dual power against capitalism, statecraft, and hierarchy more broadly by using communalist means, structures, and processes to develop communalist ends. Communalism involves oppositional politics and direct action–opposing that which ought not exist and taking action without being mediated by hierarchy within one’s own organization. Another dimension of communalism is reconstructive politics and mutual aid–developing social freedom and meeting people’s needs through horizontalist organizations and actions that pool skills, tools, needs, abilities, resources on various scales and creating alternative institutions and infrastructure. Another important goal is popular education–internal and external to communal assemblies. It is important to create a form and content of communalism and that requires convincing people through reasoning of libertarian socialist practices–such as direct democracy and non-hierarchy. An important way to do so is to focus together on common needs and common struggles and to use argumentation for why horizontalist self-organization, mutual aid, and direct action etc. can help arrive at various goals people have better than other means (such as hierarchical ones) and why libertarian socialist methods (direct democracy, mutual aid, direct action, etc.) are more ethical and effective at arriving at various things that people value.

Communalist assemblies and embedded pariticipatory councils can develop oppositional and reconstructive politics at the points of extraction, production, distribution, reproduction, and community life. Community assemblies and embedded councils can develop, help with, and participate in many different kinds of oppositional and reconstructive politics. This includes everything from direct action such as occupations of hierarchical infrastructure, full on expropriation of land, means of production and fruits of labor, civil disobedience, rallies, strikes, blockades, boycotts, insurrections, marches, community self defense, to mutual aid such as things like free food distribution, free resource distribution, developing people powered infrastructure, etc.

The process of developing a libertatory ecosystem of collectives is done in part through developing embedded councils /working groups of community assemblies. However, it is also through incubating and/or assisting various groups–such as other communal assemblies, community and worker controlled cooperatives, solidarity networks, direct action collectives, mutual aid networks, community gardens, popular education organizations, free stores, tenants’ assemblies, radical unions, ecological technology projects, issue specific groups, and more. These building blocks can collaborate to help each other out mutualistically and create alternative and counter institutions to business as usual.

Communal assemblies–outside of developing their own projects– can coordinate with and incubate organizations rooted in direct democracy, direct action, and mutual aid. Together, such building blocks can join up to become more than the sum total of their parts in mutualistic relationships. Such a strategy can integrate more fragmented movements while uniting them on terms of unity that are in harmony with libertarian socialist practices. In a sense, communalism is to community organizing as anarcho-syndicalism is to workplace organizing.

As such building blocks of a potential dual power start developing, they can coordinate and form alliances and joint-projects and actions. As communal assemblies start developing across different blocks, neighborhoods, cities, and regions, they can form more formal co-federal structures of community assemblies on various scales. Such projects aim towards decentralizing power, meeting people’s needs, while building horizontalist governance structures to replace hierarchical governance structures, before, during, and after revolutionary moments.

The above approach is prefigurative in the sense that such communal assemblies and self-managed institutions try to model the world they want to create in their formal structures and processes, but it is also strategic in the sense that it realizes that the new world does not exist yet and is something that we need to build from the conditions that exist. The formal features of communalism are necessary but insufficient for communalist goals. Although it is of course true that instrumental strategic reasoning without due ethical considerations can lead to brutality, merely prefigurative approaches–especially ones that don’t realize a distance between means and ends, and not just where there should be consistency between them–can lead to toothless projects with no meaningful attempt to re-organize power and confront hierarchical conditions. Given the current conditions, questions like “how do we reach out beyond the current left and organize with the unorganized?”, “what collectives should we try to build?”, “what collectives already exist that we can work with on various levels?”, “how do we spread popular education?”, “how do we keep our eyes on the prize while engaging in intermediate steps?”, “how do we link short term and long term goals?”, “which project should we focus on with our current levels and limits of capacity?” “how do we reach out without sacrificing what should be minimal principles?”, “how do we use our collective capacity in a way where we become more than the sum total of our parts?” etc. are just some of the many important questions one should be asking oneself and one’s comrades when organizing a communalist project.

ByLaws:

Bylaws should be fleshed out as a communalist assembly develops. A good initial aspect of the bylaws is some kind of decision making process. This can be as simple as follows:

- Decisions ought to be made through deliberation. Critiques, agreement, dissent, amendments, counter-proposals, etc. should be included as well as attempts to round out decisions through dialogue. The assembly tries to develop consensus. When there is not a consensus, then the decision is further deliberated upon and then gets put to vote.

- If consensus is not arrived, at then decisions ought to be made by simple majority–decentralizing decision making and veto power.

- Proposals and Decisions ought to be filtered through the constitutions/bylaws/bill of rights and/or points of unity for process. *and such constiutions/bylaws/bill of rights/ should be rooted in direct democracy/non-hierarchy/co-federation/etc.

- Committees, delegates, etc. must be administrative rather than make policy over and above the assembly. They are to self manage within the mandates from the general assembly.

- Committees and delegates are to be subject to immediate recall by the general assembly.

This can be fleshed out and adapted as needed. Focusing too much on bylaws at the beginning can turn people away and also become overly process oriented. However, not having a good process can lead to hierarchical and arbitrary power instead of a clear horizontalist democratic process. It is important to use a sufficiently ethical and practical process to develop actions and ends worth developing– rather than a reductive focus on process. Having some kind of liberatory structure from the beginning for people to agree to, tweak, adapt, can help set a project up on directly democratic terms. It is important to think about deliberation and decision making processes, transformative and restorative justice processes, various delegate positions, and ways that committees and affiliated organizations relate to the general assemblies etc. as these kinds of things will come up in the process of organizing.

The overall policy of a communalist project is decided by the general assembly and embedded committees then self manage the implementation of that policy within the boundaries set by the general assembly. Individual delegates would have no policy making power and would serve purely communicative, coordinative, and administrative roles within their mandate. Such roles should be rotated and there should be a fostering of general knowledge throughout the assembly project about how to do various roles. Part of the assembly project is a process of education for those involved to find out how to self manage an organization. People bring their different propositional and practical knowledge to the table and the assembly should serve as a teaching and learning experience for all involved as people work on shared projects.

Embedded Councils/Committees/Working Groups:

When there is a project voted on at an assembly, an embedded council/committee/working group can be started to then implement the project. The implementation of the project should be within the bounds of the policy made from below (by a community assembly or co-federation of assemblies). The committee–formed of volunteers who agree enough with the policy made from below (a policy that is at least in harmony with minimal libertarian socialist processes and practices)– then self manage the implementation of the policy and report back to the community assembly project that it is a part of. Committees can have broad or specific mandates–and depending on the specific decisions and contexts, the mandates should be more specific or more broad. For an example, a direct action or solidarity network committee of an assembly might be given the broad mandate of 1. Organizing according to applicable bylaws, bill of rights, points of unity 2. to take direct action against landlords and bosses 3. Towards mutual aid for tenants and workers and 4. as A direct action wing of a general assembly that can do (or agrees to do) X, Y, and Z actions/kinds of actions (otherwise further deliberation with assembly would be needed for a specific action or kind of action to be done by this committee of the assembly) 5. that Reports back to and is accountable to the assembly. Responsibilities from the assembly to the working group can be expressed as well which could look like 1. specific or general assistance from an assembly and other collectives within the assembly, 2. the assembly helping to promote and mobilize for specific direct actions during meetings 3. use of broader communications infrastructure of an assembly for promoting specific actions, etc. It will make sense to make some committees open to all members (or non members), and to make other committees closed (where only those delegated from the general assembly can join).

Sometimes it makes more sense for strategic reasons for some committees to eventually develop into relatively separate organizations. This can be a really positive thing for the working group project and the assembly project and even an initial intention of some working groups of assemblies (for example when an assembly has limited capacity and needs to focus on some projects and not others, when the working group makes more sense as its own membership organization, etc.). However, depending on the context, full separation from the assembly and other affiliated organizations can be an inhibiting factor for both the assembly and the other collectives because of benefits they can all gain from each other– including but not limited to mutual aid between groups, collaboration between groups on joint projects, developing an ecosystem of collectives that work together and are part of a greater project than any specific issue, etc. Instead, it can makes sense for some committees that no longer make sense as full on embedded councils of community assemblies to become affiliated autonomous organizations– working together with the assembly project in some kind of way when it makes sense for common goals. Whether a specific project should become embedded within assemblies, affiliated with assemblies, or separate from assemblies will vary from project to project and context to context. On one level ecosystems of liberatory organizations and movements are needed, but if different groups do not strategically combine forces to row in a similar enough and mutualistic direction, then movements can be limiting their potential and even acting in a way that is less than the sum total of their parts!

Under full communalism, politics and economics would be integrated into co-federated networks of horizontalist communes with embedded self managed councils for implementation of communal decisions. The embedded councils would be made out of volunteers who self manage within policy made by the community assembly or co-federation of community assemblies–assisted by liberatory technology. Auxiliary councils and groups–in harmony with libertarian socialist and communalist rights and responsibilities– would also exist. However, it is important that such auxiliary groups do not privatize the means of existence and production needed for reproduction of political economic life, horizontalism, and communal self management. Production would be for needs, desires, and use. And accordingly, distribution would be according to needs, desires and use where all would have access to a cornucopia that is reproduced and developed by participatory labor, work, and action assisted by ecological and liberatory technology– including the automation of toil and the elimination of roles that don’t serve a good social function (such as cops, bosses, salespeople, the entirety of the fossil fuel industry, etc.).

Delegate Roles:

Although communalism is against any kind of representative policy making, communalism is not against coordinative, communicative, and administrative roles. Such roles should be mandated and recallable and have no policy making power. Such roles should be rotated–so no one person has to do too much work and so everyone gets as much general knowledge as possible. Sometimes it can make sense for some roles sometimes to be done by co-delegates. Such roles can include things like a secretary or note taker position, a treasurer position, a digital outreach coordinator (emails, website, social media, etc), and co-federal delegates to coordinate between assemblies and then go back to the assembly base where actual decisions are made.

A crucial goal of delegates, outside of the functions they are delegated to do, is to organize themselves out of their positions and make sure the torches gets passed on– along with the knowledge needed for their roles. One way to do this is to stagger the role so the new person coming into a delegate role learns from the prior delegate. Delegates can exist through nomination and self nomination and then a vote (or lack of dissent). Some kind of spinning role chart (that passes applicable delegate roles in a circle overtime between all members of an organization) or sortition process might also make sense for some delegate roles in some assemblies. In the above processes people can opt out of specific delegate roles, but such processes can encourage shared labor, shared knowledge of how to do various delegate functions, and encourage people and assemblies to not turn such temporarily held roles into something permanently occupied by anyone. The more the social reproduction of an assembly is shared among many participants–within and outside of specific delegate roles– the more resilient that overall project will be (all else being equal).

Before one starts a Communalist Project:

Before a communal assembly project launches, it is ideal to have people who have some shared principles to do some preparation work together. It is good to have a core group of people who understand the basic strategy of communalism. It might make sense to even start as a reading group to review the basics of social ecology and to theorize what it would mean to apply communalist praxis to one’s specific location. It can be helpful if the people helping you start an assembly have various kinds of diversity within them and diverse and differentiated social relations for both ethical reasons of inclusion and strategic outreach.

Before one brings a communalist project to the public, it can make sense to have some kind of pre-drafted idea of the structure and orientation of the project–however skeletal it may be. This idea and project can then be proposed to and adapted by people who are interested in co-authoring a communalist project. Depending on the context one is in, one can adapt the bylaws, bill of rights, or points of unity for practice to be more and less fleshed out– fleshed out enough to be coherent but flexible enough to be adaptable and to include a large realm of permissibility within the bounds of essential communalist processes and practices. Although the following will have to be deliberated amongst people and adapted to needs and preferences of participants: having a consistent meeting space ready, a proposed structure (which may or may not include skeletal versions of bylaws, bill of rights, points of unity for practice, program, strategy, etc. to propose), an outreach plan, some initial projects that can be started, and adequate time to really think about how to launch the project can all be useful before starting a communal assembly.

It is important to find people already very sympathetic and then reach out to de-politicized or more moderately politicized people–that is to reach inwards for the express purpose of gaining capacity to reach outwards with such a specific project. However, communalist assemblies strive to be popular organizations rather than ideologically specific groups or “lower common denominator of the left” kinds of organizations. The goal is to reach outwards to people through an assembly project without compromising on what should be minimal practices of communalism.

An organization can only launch once– it is best to plan how it is strategically introduced to the public. However, the starting point is distinct from its overall developmental potential and is just one of many features to think about when developing a community assembly. It is almost always more sustainable long term for a group to start out moving at a slow pace–working on short term goals and tangible achievable projects through horizontalist processes– to build themselves up before they more fully reach out and take on more difficult projects. It is also possible to start a communalist project too slowly– to the point where important moments get missed where it would have made sense for a project to have already been introduced to the public and/or already tackling larger scale issues. No amount of prior planning will be able to exhaustively deal with the turbulence of putting theories into action, but thinking about how to develop a meaningful beginning and trajectory is far more fruitful than throwing darts at a board in the dark.

Sometimes it makes sense to start a community assembly– or movement assembly– around a specific issue or project that people are interested in. Other-times it makes sense to start assemblies to find out what issues or projects should be focused on. Both approaches have pros and cons. Single issue based projects can lead to getting pigeonholed into particular areas that are reductionist compared to the wide array of content assemblies can enact. Starting with assemblies to find issues to develop together can be too vague and abstract to motivate people at first. Overtime, both assemblies and specific projects that they focus on need to develop in tandem and the way a specific assembly starts is less important than how it develops.

Research/Community Mapping:

When starting such a project, one should look at potential comrades and people trying to stop a communal assembly project from happening. Look at the other building blocks of an ecology of movements in one’s own locale. It might be an IWW branch, a local libertarian socialist group, a direct action network, a mutual aid network, cooperatives, ecologically oriented groups, community spaces etc. Look at local problems and aspirations people have to see what projects make sense. Even though communalism ought to be a secular project including freedom of and from religion, reaching out to left leaning religious congregations–and members of other congregations– can be an important thing to do. Find out people and organizations that might be sympathetic so they can be invited to assemblies.

Research various “pressure points” of hierarchical systems in your area and various ways action can be applied by popular movements to achieve liberatory goals. Research far right organizations in your community. Be aware of who the local ruling class are. Research potential for police repression in your area and generally. Although there is general research one can do that will be relevant to organizing in a particular context, research and community mapping should be adapted to specific projects and goals and integrated as part of strategy in assemblies and embedded councils.

Outreach:

Outreach can be done in a plurality of ways. Word of mouth, face-to-face , and one-on-one interactions and communication are very important. One-on-one outreach can also be done via one on one text invitations. Door-to-door approaches are underused and very effective at reaching out beyond the already existing left. Flyering is important as well–whether or not one lives in a city that has a culture of flyering for events. Bus-stops, neighborhoods, cafes, walls for postering events throughout cities, etc. should be flyered as much as possible when trying to do outreach. Make sure that the flyers include relevant information about the organization, some explanation of what the event is, as well as the time and space location of the event, and where to find more information. Handbill flyers can be made to pass out to people at various political, countercultural, subculture, and common spaces, every day events, and while people run into people throughout their everyday travels. Handing out handbills and flyers to many people and/or creating flyering teams and work parties can help make the such processes enjoyable and shared. Announcing an event during announcement sections of groups that are fine with announcements for other groups can also be fruitful. Potlucks and Block parties can also be good ways to do outreach and build community as part of a community assembly project. Do not underestimate the potential of collective action projects to help build community for further actions. The internet is an important tool as well–but has many limits. Text message groups, social media events, and internet groups can be used to reach out to people and do in-reach–but they should never be relied upon at the expense of face to face organizing. Having an email list-serve is an important tool to utilize for in-reach. And of course outreach through direct action and shared participation in social struggles is also indispensable.

Many people are not initially radicalized (as in activated to get involved in transformative politics) by going to meetings, but by going to direct actions. Many people are initially radicalized by mutual aid projects instead of direct actions. Many people are initially radicalized through popular education rather than through any of the above, etc. It is often when people deepen their understandings of activities within the processes of direct actions, mutual aid projects, and popular education that people often see the importance of going to meetings, making collective decisions, and doing the activities that make popular organizations, direct actions, and revolutions possible.

Initial projects one Can Start:

Exactly what projects to begin with can be tricky, and is not identical across different contexts. One way to start community assemblies and projects within assemblies is to host issue focused forums and assemblies where single issues are deliberated about in depth. Alternatively, people can start with an open assembly to find out what to focus on. One function communal assemblies are able to do particularly well is prefigure the commons (means of existence production held in common accessed freely according to needs) via communal self-management. However, to meaningfully develop the commons on a large enough scale, the means of existence and production must be seized from hierarchical rule. Mutual aid projects of some kind are often ideal projects to start. They are usually lower risk than oppositional political actions (not that “low risk” is the only thing to take into consideration). Mutual aid projects– the use of horizontalist organization to meet people’s needs via multi-directional support– lead towards mutual thriving of persons involved while disproportionately helping those in poverty and otherwise most in need. And mutual aid projects do the above while using a horizontalist forms, participatory organizing, with communistic content. Additionally, mutual aid projects are generally the most agreeable possible projects! Oppositional direct actions are usually more controversial and usually involve more risk. That being said, direct action arms of community assemblies are important to bridge abstract problems and solutions to concrete actions that can be done as well as give the assembly a class struggle and class abolitionist ethos. If assemblies lose an oppositional character entirely, then they can easily become pejoratively utopian. Direct action committees of assemblies and Solidarity Networks are ways that people can take action against the state, capitalists, bosses, and landlords in ways that use direct action towards meeting people’s needs. Sometimes because of various conditions (urgency, theoretical composition of people, strategic openings, for strategic reasons wanting the assembly to start with an explicit class struggle approach etc.) direct actions make the most sense as starting places for communalist assemblies to organize around. In other time space locations with different social relations, community gardens, community technology projects, community infrastructure development, and community-cooperative development might make more sense as the most initial projects to start. Fundraisers for political events, potlucks, and block parties can be ways to build community, have fun, and spread political messages through political causes, pamphlets, relationships, and dialogue (and are relatively easy to do). Skillshares, lectures, reading groups, and other popular education projects can help facilitate theoretical and practical knowledge and can serve as social gatherings for further organizing and can help people do better actions in the future through learning better theory and critical thinking skills. Despite mutual aid projects often making sense as the first projects community assemblies start, there are many good first projects communalist assemblies can start and no uniform formula for what problems should be tackled first and what projects should be started first.

One of the strengths of community assemblies is their potential to do a lot of different types and sub-types of activities. However, this can also be a strategic weakness of community assemblies if this is not utilized well; for if community assemblies are “biting off more than they can chew”, they can wind up squandering effort in many projects that do not have enough capacity. Inversely, “planting a plurality of seeds” can allow some to blossom. Finding ways to strategically row the communal ship together requires adjusting how many projects an assembly takes on overtime as well as which projects an assembly project takes on.

Where to start: Block by Block or more city wide organizing?:

One way to start communal assemblies is going block by block to organize specific blocks and neighborhoods into block assemblies and neighborhood assemblies. Another way to begin such a process might be to organize a broader city wide assembly project of some kind and then decentralize into neighborhood assemblies and block assemblies as people join and capacity allows–and as people find out which particular blocks they want to focus on. If one is starting with a block by block approach to organizing, then people should most fundamentally organize where they are and where they go. However, some neighborhoods and regions within a city that more fruitful for organizing and are important to focus on–due to both economic and theoretical compositions of various neighborhoods. Working class neighborhoods are the most important neighborhoods to organize–as well as neighborhoods that have good class consciousness and are more left leaning in general (and those initial groups can help the assembly model spread elsewhere). However people can and should start liberatory organizing wherever they are– and wherever they go. Common needs, common struggle, and common values are different bridges that can lead towards communalist practice.

There is an important urgency to change the world and therefore we must take our time with these projects and build them in a generative way. Do not expect the assembly project to be successful overnight. Although more periodic kinds of groups that only exist for a few months–and institutions that only last a few years–can do a lot of good actions within a city or area, organizations that continue onward many years beyond their initial jumping off point, that are ethically prefigured with a strategic content, can potentially arrive at long term sustained goals and even revolutionary goals.

General Principles and Particular Contexts:

Communalist assemblies can be started in a variety of ways. Different approaches of applying general principles make more and less sense in different contexts. The general principles of communalism are necessary but insufficient for their application to particular conditions. The cutting edge of communalist praxis deals with applying the general principles to particular contexts and creating strategic content with tactics appropriate for such strategy. This is where things get relatively tricky and where general theory and approaches fail to be a sufficient guiding path–as necessary, desirable, and important as they are. The ethics of communalism can adapt to various geological, ecological, preferential, social, political, economic, historical, cultural, and individual differentiations while still retaining its essential features. And the only way to make such a path is by organizing together with people using communalist processes to solve political economic and social problems and co-create collective decisions and actions.

Applying libertarian socialist communal assembly projects will look different in different places despite retaining general lower common denominators. Even though there might be surprising similarities about applying general principles to particular contexts, Applying such principles in Oakland will look different than applying such principles in New York City, which will look different than applying such principles in Jackson, Mississippi, which will look different than applying such principles in rural Vermont, which will look different than applying such principles in Kobane or Mexico City. Such locations are also not static communities; they are in process, so within a few years the best ways to apply such principles to particular locations might significantly change. Ways of applying general principles to particular contexts–and even the general principles themselves– are subject to change if there are sufficiently relevant variables that emerge. There are always ways to implement communalist projects in better ways– even compared to projects that are doing well.

Shared conditions vs. shared principles vs shared practice:

Not having sufficiently coherent form or content can create incoherence to the point where the assembly subverts its own liberatory features. A way to round out an assembly or a collective without making the group based on shared ideology is to have common practices rooted in libertarian socialist principles embedded in the structure, constitution, bylaws, bill of rights, and (as much as possible) culture of an assembly. Not everyone has to agree to libertarian socialism or communalism to agree with terms of practice that are in harmony with libertarian socialism or communalism. Such an approach has a lot of the benefits that a shared ideology approach has yet is nonetheless distinct and serves different functions.

One of the goals of a communalist project is to reach out to people who do not yet share communalist theory. Putting forward programs and points of unity that groups should be rooted in and bounded by, if not done well, and adapted to the specific kind of organization one is trying to build and context one is in, can unnecessarily inhibit reaching out to people who do not already agree. For example, imagine how unnecessarily alienating it might be to ordinary people to start a community assembly in the USA in 2019 that starts with a program calling for “full communism” with that exact wording. It would make more sense strategically, for the sake of communication, for the program to talk about giving everyone free necessities of life, developing a commons, mutual aid, self-managed economics etc. We need to find ways to communicate communalist principles and practices, have them enshrined within the structure and alive in the content of popular assemblies, without unnecessarily alienating people and without making communalist ideology (a specific kind of libertarian communism) a prerequisite for joining such assemblies (and without sacrificing the ethical and strategic substance of communalist practice at the same time).

There is no one size fits all approach to how people get involved in social movements and start participating with others. Common conditions, and/or desires and/or principles can develop into shared practices and organizations, and such a process can nourish shared principles, and from there those new shared principles can nourish future actions, etc. If sufficient common ideology exists between people, it is possible for specific kinds of shared ideology based organizing to happen (that can be done via ideologically specific libertarian communist groups distinct from popular organizations but with members who are participants in both). Such ideologically specific groups can create social movement groups and popular organizations. Additionally, members from ideologically specific groups can join social movement groups and popular organizations and advocate for direct democracy, direct action, mutual aid, etc. within social movement groups and popular organizations to help those already existing groups achieve their own goals. The libertarian socialist strategy of doing so has been called “organizational dualism”, and it aims towards the self management of popular organizations and social movements rather than a hierarchical vanguardist approach.

What might inhibit Communal Assemblies:

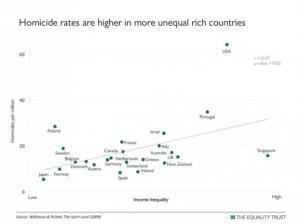

Inhibiting factors of communal assemblies will differ from region to region over time and space. Capitalism and the state are some of the greatest inhibiting factors, for they cause everything from a lack of public space to organize in, lack of access to the means of existence and production, to cops enforcing unjust laws, etc. Rightwing populists and reactionary formations inside and outside of the state will be particularly violent towards leftward tendencies. There is of course TINA–There is no Alternative– a prevailing theoretical and practical orientation that inhibits any radical critique of that which exists . Liberal cooptation is another thing to be wary of given that liberal ethos can take libertarian form and subsume it to liberal content (or form). The democratic party has a whole array of activists and movements that spread electoral reductionism that can try to take over and defang leftist organizations. Marxist-Leninist tendencies can try to restructure communal assemblies into hierarchical forms aimed towards state socialist revolution, whereas anti organizationalism will try to inhibit collective decision making processes and organizational structure altogether. Racism, sexism, Anti-Semitism, etc. are inhibiting factors that make it difficult to build relationships and trust to work together on common issues and issues that drastically affect some people more than others. Furthermore, such racist, sexist, and oppressive relations inhibit the kind of egalitarian relations needed for a project to be worth fighting for. Such issues exist both within the wider society and within left circles. Identity-reductionist attempts to deal with oppression lead to ways that are not holistic enough to build solidarity–and such approaches do not know how to deal with political economic structures that underpin structural forms of oppression.

Communal assemblies should embody general communalist principles and adapt to particular contexts they are in and surrounded by–not just either or. Furthermore, communal assemblies should be both prefigurative–in the sense of building and reproducing the kinds of structure that ought to exist in the new world–and strategic in the sense of being oriented towards certain principled goals and trying to achieve them rather than mere development of a good process/structure. The strategic aspects should be in harmony with good principles rather than at the expense of them.

Communal assemblies should also build relationships with people and not just be a political process. The development of a culture of care, mutualistic friendship, and trustbuilding are important steps to actual decision making processes and organizational resilience– and developing a good society! However, such assemblies should not devolve into a mere politics of friendship– people do not have to be close friends with one another to work meaningfully together politically on shared goals through shared processes.

Communal assemblies can also be inhibited by decisions made by communal assemblies themselves! This can happen through decisions that inhibit horizontalist form, lack of strategic content, lack of good relations between persons, lack of prudent vision (which CAN take the form of a focus on militancy at the expense of reaching out), not reaching out to people, not educating people, not having good enough structure, etc. No matter how good the form of an organization is, it does not necessarily entail good content. Even if good form and points of unity for practice are carried through within the content of an organization, the content itself might not be strategic and generative towards long term goals.

Is the Assembly the best place for you to start?:

Although communal assemblies are an important–in my opinion the most important– building block for revolution (that can also catalyze other building blocks), they are also not necessarily the best form for every particular group of people to start as the first project they do within every particular context they are in. It might make more sense to build other building blocks of a revolution first such as a solidarity network, a tenants’ union, a houseless solidarity organization, a mutual aid organization, a cooperative federation, a popular education group, an ideologically specific libertarian socialist group etc. It is easiest to start a communalist assembly when liberatory organizations and cultural dimensions already exist. However, communal assemblies can act as a catalyst for those very institutional and cultural shifts and can be a great project to start even when there is not already a broader left social movement ecosystem.

Learning from history:

Fortunately, when starting a community assembly–or some other kind of popular organization– we do not have to completely reinvent the wheel: Looking through history we find many ways different democratic and communal projects have made decisions together, have increased various social health criteria, happiness, and freedom, and various ways such projects have fallen short of their most liberatory goals. There are important lessons we can find throughout the history of human freedom. Looking to revolutions such as Rojava, The Zapatistas, anarcho-syndicalist Spain, Shinmin Korea, and the Free Territory are especially helpful. We can glean the various lower common denominators and particularities of each of the above movements and see what parts of the above revolutions make sense for us to apply in our specific contexts. The history of freedom is far more expansive than libertarian socialist revolutionary history: it includes thousands of egalitarian societies throughout history across many cultures, regions and continents. The history of freedom also includes issue specific social movements, the history of syndicalism, the broader history of anarchism, socialism, communism, the left, and far more. It would be foolish to not glean gems from revolutionary history. However, this can only be done well through critical investigation of history– including a critical evaluation of one’s favorite revolutions and societies in history. A good analysis of history would characteristically help with a good understanding of what the universalist principles and practices of communal and democratic relations are– as well as what the more contingent principles and practices of various communal and democratic relations are. A good analysis of history combined with good contemporary praxis will be able to remix the right principles and practices from history and adapt them to one’s specific context as new, unique, and uncharted relevant variables emerge. As we learn from history we must also remember that the answers to future problems have not been exhaustively answered by the past. Such an analysis would try to find anti-liberatory dimensions even in the most liberatory of organizations and movements–as well as strategic and tactical blunders made by various revolutionary groups. This would not be to do an unfair rejection of their most positive elements, but it would be to avoid the kind of non-critical cheerleading that inhibits us from seeing imperfections and ways specific and general projects can do better according to good ethical criteria.